Submission: What’s wrong with the RICA bill

Intelwatch prepared this submission to South Africa’s Parliament on the RICA bill (the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-related Information Amendment Bill).

Download the submission as a PDF here, or read it in full below.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 ABOUT INTELWATCH

Intelwatch is a non-profit organisation dedicated to research, policy work and advocacy to strengthen public oversight of state and private intelligence agencies in Southern Africa and around the world. Founded in 2022 in South Africa, Intelwatch aims to carry forward the work of the Media Policy and Democracy Project, which was a research collaboration between the Department of Communication and Media, University of Johannesburg and the Department of Communication Science, University of South Africa, which contributed important policy research on surveillance issues in Southern Africa, and South Africa especially.

1.2 OVERVIEW

We welcome the introduction of an amendment bill to the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-related Information Act (Rica), albeit delayed. The Constitutional Court judgment in amaBhungane[1] and the High Court judgment which preceded it were a vital step towards surveillance reform in South Africa, with resonance far beyond our borders. This has followed, and ran parallel to, nearly a decade of policy engagements and research outputs by Intelwatch and its predecessors, drawing on a growing body of evidence which showed that Rica’s lack of safeguards and outdated approach have enabled surveillance abuses, undermined public oversight, and failed to protect constitutional rights.

With this in mind, the Bill’s minimalist approach – narrowly focused on meeting the bare requirements of the court’s order – is deeply regrettable.

As we detail below, the Bill falls short of offering the necessary reforms to Rica, including those demanded in the amaBhungane judgment and other long-standing issues which pre-date the litigation, and which the Department of Justice has long known about and pledged to address. We submit that Parliament must address these issues in the Rica Bill or risk a continuation of the same abuses and policy failings which brought Rica before the Constitutional Court in the first place.

The views in this submission are informed by the norms developed through the course of research and policy engagement on Rica, detailed below, and guided by international standards on communications surveillance and human rights – most notably, the International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance (the “Necessary and Proportionate” principles)[2].

In the section below, we give a brief overview of previous policy engagements on Rica, after which our submissions on the Bill itself are structured as follows:

- The ‘Section 205’ loophole: This concerns the absolute need for Rica to be amended to address the parallel procedure, in section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act, for law enforcement officials to access communication data with none of the existing safeguards built into Rica, or the additional safeguards required by the amaBhungane

- The need for a panel of judges: This concerns shortcomings in section 15A of the Bill, which currently restricts the appointment of Rica judges to a single judge and does not address resourcing challenges which have undermined judicial oversight in terms of Rica.

- Shortcomings of the ‘Review judge’ solution: This concerns shortcomings in section 15B of the Bill, which provides for a review judge to automatically review the decisions of a Rica judge. This formulation does not address the Court’s order on the need for safeguards to address the ex parte (one-sided) nature of Rica interception decisions.

- Providing an appropriate term of service: This section gives brief recommendations to provide for any Rica judges and review judges to be appointed for a fixed five-year term, based on international best practice.

- Post-surveillance notification: This addresses the concern that section 25A(2)b waters down the provision for post-surveillance notification, and proposes the Bill give further guidance to ensure meaningful detail and a standardised format for any such notification.

- Data management: This section gives brief recommendations to strengthen the Bill’s provisions for data management procedures.

- Need for guidance on oversight reporting: This section outlines the need for the Bill to provide for guidance and standards on reporting functions by Rica judges and other entities involved in interception, and to make provision for service providers to make annual transparency disclosures.

- Concerns on provisions for mass surveillance in a parallel legislative process: This draws attention to the re-introduction of mass surveillance in a parallel legislative process, the General Intelligence Laws Amendment Bill (2023), also before the National Assembly. While this falls outside of the Committee’s work on the Rica bill, we outline how this parallel process is at cross purposes with the objectives of this Bill and threatens to undermine the Committee’s work.

1.3 HISTORY OF ENGAGEMENT WITH THE DEPARTMENT

Before turning to the Bill itself, a brief overview of policy engagements leading up to this point is needed in order to contextualise the unfortunate decision by the Bill’s drafters to confine their amendments to such narrow grounds.

These engagements took place in the context of mounting evidence and case studies that the state’s surveillance powers have been subject to abuse, which we will not repeat here, save to point out that targets have included investigative journalists, including incidents unrelated to the amaBhungane case,[3] government officials and political figures,[4] and apparently a number of civic groups and political formations.[5]

The Media Policy and Democracy Project (MPDP), the forerunner organisation to Intelwatch, submitted a preliminary analysis of Rica’s misalignment with international standards to the Deputy Minister of Justice and Department officials in 2016.[6] In 2020, MPDP published, among other things, recommended reforms to address the lack of safeguards relating to the use of communications data in policing (the section 205 ‘loophole’, detailed below).[7] In May 2023, the Media Policy and Democracy Project and Intelwatch made further research submissions to the Department which outlined policy recommendations for reforming Rica in the wake of the amaBhungane judgment, drawing on international standards and best practice.[8] This represents a commendable ‘open door’ approach from policymakers, which we appreciate. However it must be noted that the issues raised in this submission are not new.

At the same time, the Department and Ministry have long pledged to address many of these issues:

- In 2015, the Rica judge at the time noted in her report to Parliament[9] that the Department had various amendments to Rica on its legislative programme for 2016/2017.[10]

- In May 2017, a department spokesperson told the media there was already a process to revise Rica, and would consider section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act in its revisions.[11]

- In June 2017, in reply to a written question in the National Assembly the Minister stated that Rica had been earmarked for amendment, and that the Department was still “in an investigative and initial drafting phase;” the Minister again noted concerns relating to the use of section 205 of the CPA to access communication data, said the department would consider amendments in this regard as well.[12]

- In the litigation on Rica itself, various representatives from the Department and the Ministry urged the court not to rule on Rica’s constitutionality as there was already a policy review underway, which could result in a draft bill by August 2019.[13]

Suffice to say, except for the current Bill, no amendment process has come to light, and the current Bill also does not seek to address any of the known issues except for those deficiencies specifically identified in the Constitutional Court’s decision.

We turn now in the following pages to specific provisions and omissions in the Bill which need to be addressed.

2. COMMENTS ON THE RICA BILL

2.1 THE ‘SECTION 205’ LOOPHOLE MUST BE ADDRESSED

Summary: The Bill misses a crucial opportunity to close a parallel procedure for accessing archived communication-related information (communication data), in section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act. This loophole has enabled law enforcement agencies to access sensitive communication data without any of the safeguards and restrictions which apply to Rica. The Bill must remove this parallel procedure to meaningfully apply the safeguards intended by the Constitutional Court, and by Rica itself.

Possibly the gravest problem with the Rica Bill is that it fails to address the biggest gap in safeguards and protections on surveillance: the parallel procedure for law enforcement officials to access people’s phone records and other communication-related information through Section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act (the CPA). This is enabled through section 15(1) of Rica, which provides for “other procedures for obtaining real-time or archived communication-related information”, and section 59, which amends Section 205 of the CPA to that effect.

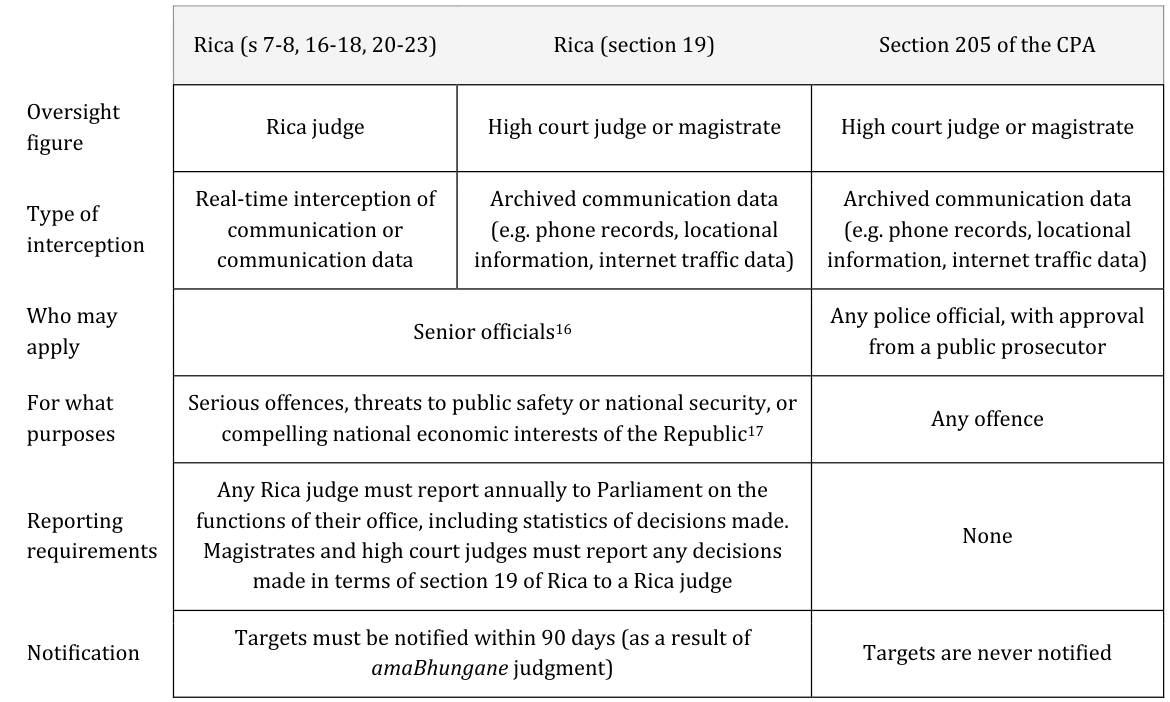

In terms of Section 205 of the CPA, any local or regional magistrate or high court judge may issue a subpoena, at the request of a public prosecutor and a police officer, for ‘archived communication-related data’, commonly known as communication data or metadata. This could include extensive categories of sensitive information, such as a person’s cell phone records, for example, or the locational history of their mobile device, or internet traffic data. Section 19 of Rica already provides for law enforcement agencies to apply to a high court judge or local or regional magistrate for permission to access this type of information, but subject to relatively stricter safeguards. These are unpacked below:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, law enforcement agencies use the section 205 procedures exponentially more than the equivalent powers in Rica. (See annexure 1.) The lack of safeguards in section 205 procedures are particularly concerning given the growing appreciation that communication data is just as sensitive, and often even more revealing, than the ‘contents’ of a communication. For example, the communication data held by MTN, Vodacom, or Cell C about each of their customers would likely reveal where they go each day, who they interact with, and where they sleep at night: these lines of information can give detailed insights to a person’s political activity, their personal life, their legal or financial liabilities, and their private indiscretions. A journalist’s phone records may reveal their confidential sources; a police investigator’s phone records may expose informants or whistleblowers.[14]

Acknowledging the risks of this parallel procedure, in a 1999 review of Rica’s predecessor (the Interception and Monitoring Prohibition Act of 1992) the South African Law Commission recommended that section 205 of the CPA should not permit requests to access communication data.[15] However when Rica passed into law, the parallel procedure was kept.

The lack of safeguards on section 205 procedures have led to known abuses: for example, a journalist, Athandiwe Saba, discovered that a police officer in Pinetown had seized six months of her phone records through a fraudulent Section 205 request (in an alleged ‘housebreaking’ investigation). Those phone records later fell into the possession of a scandal-plagued public official she had been investigating.[18] In a separate incident, the NPA sought to prosecute a former captain in SAPS Crime Intelligence for various offences relating to alleged ‘moonlighting’ as a private investigator; prosecutors alleged that he had used fraudulent section 205 subpoenas to acquire the phone records of senior legal figures and high-ranking SAPS officials.[19]

Quite simply, as long as section 205 procedures exist in parallel to Rica procedures, without any of the necessary safeguards or oversight, it is likely that attempts to build more safeguards into Rica procedures will simply drive more abuses to section 205. This undermines Parliament’s work, and risks making a nonsense of the court’s intentions in amaBhungane.

There is a simple fix: close the loophole. The Bill should repeal section 15(1) and section 59 of Rica, to ensure that all applications for access to archived communication-related information are sought through section 19 of Rica. This ensures that magistrates courts and high courts can continue to receive such requests, but with the necessary safeguards and restrictions that apply to all Rica procedures. Law enforcement agencies may continue to use section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act to seek access to other kinds of evidence.

Recommendation:

- The Bill should repeal section 15(1) and section 59 of Rica, to ensure that section 205 of the CPA no longer provides a parallel way to access archived communication-related information, and that Rica is the only law applying to communication surveillance, including of communication data.

2.2 THE NEED FOR A PANEL OF JUDGES

Summary: Rather than increasing the available resources for oversight, the Bill limits the appointment to a single judge. There should be a panel of judges to oversee interception applications, with sufficient resources to fulfil its mandate. Effective oversight is enabled when each request can be reviewed in detail, without creating backlogs.

The Bill envisages all interception requests to be considered by a single ‘designated judge’ (the ‘Rica judge’). This represents a narrowing of what the law allows in terms of judicial oversight; the existing Act makes provision for the appointment of multiple Rica judges at a time. Though the Minister of Justice has historically chosen to appoint a single Rica judge at a time, this has been a policy decision rather than a legal requirement.[20]

Although there are multiple interception centres throughout the country, there has never been more than one Rica judge handling applications from all of these centres, and these centres serve all of the country’s intelligence agencies (including the State Security Agency, the South African Police’s Crime Intelligence division, the Financial Intelligence Centre, and Defence Intelligence).

The Rica judge’s office has also in the past operated with a relatively small number of staff members. In the 2014/2015 financial year, for instance, the Rica judge’s office reportedly had a total of six staff members, excluding the Rica judge herself. Of the six staff members, only one was legal personnel, and the remainder were involved in administrative, financial, management, and registry duties.[21]

The need to boost the capacity of the Rica judge is particularly relevant, given indications that Rica judges are unable to trust the information put to them by law enforcement agencies in applications.[22] In the latest report from the Rica judge, judge Bess Nkabinde stated that her office struggled in the assessment of the truthfulness of the affidavits presented to her:

“Indeed, the mendacity of most of the deponents to the affidavits submitted in support of the interception direction are … a matter of serious concern as the interception judge is unable to verify the truthfulness of the statements made.”[23]

The difficulties brought about by having only one judge responsible for approving interception directions for the entire country is exacerbated by other material shortcomings, such as the absence of an electronic system to administer the process of law enforcement and intelligence agencies making applications to the Rica judge for interception directions. The need for such a system was identified as far back as 2008,[24] yet in 2021 the Rica judge reported to Parliament’s intelligence committee that the lack of such an electronic system continued to be a problem, with the manual application system “resulting in errors in identifying whether a (cell phone) number in the application (for an interception directions) is new or existing”.[25]

The office of the Rica judge has historically been under-resourced, and has not had its own budget, instead relying on the Department of Justice for funding, with requisitions being subject to approval by the Department. Challenges faced by the Rica judge have in the past included a lack of basic amenities, such as a shortage of furniture, a lack of staff mobile phones for the Chief Registry Clerk and Administration Officer (to allow them to be on call outside of office hours since they must be on call at all hours), and the absence of a mobile filing system. (The office manages top secret documents for a minimum of five years, and storage had become problematic.)[26]

Whereas Section 32 of Rica makes provision for the establishment of interception centres, and compels the minister of intelligence to equip and maintain these centres and “exercise final responsibility over the administration and functioning of interception centres”, there is no

corresponding provision in Rica compelling the state to ensure that Rica judges’ offices are adequately resourced and operational. Instead, these aspects are determined by departmental policy and budgetary limitations.

There are also risks to an oversight system that incurs delays; any backlogs or delays in the administration of oversight in terms of Rica creates incentives for law enforcement officials to bypass the Rica judge or find other (potentially unlawful) avenues to conduct their surveillance.[27] Oversight must therefore be both thorough and efficient.

History has shown the Rica judge cannot rely on the integrity of law enforcement or intelligence officers in relation to the veracity of applications for interception directions. It has also shown the judges’ work is hampered by a lack of human and material resources, equipment, and infrastructure. As long as the Rica judge is not adequately resourced to deal with interception direction applications, the oversight functions envisaged in Rica will likely be compromised. In addition, without an adequately functioning electronic interface for interception direction applications between the Office of Interception Centres and the Rica judge’s office, processing and record-keeping will remain a challenge.

Recommendations:

- The Bill must provide for multiple judges to be appointed to oversee Rica decisions.

- The Bill must make provision to ensure adequate resourcing for all Rica judges.

2.3 APPOINTING A REVIEW JUDGE DOES NOT ADDRESS THE COURT’S RULING

Summary: The Bill needs to provide for an independent ‘public advocate’ to address the ex parte (one-sided) nature of surveillance applications, as a growing number of jurisdictions have done. The Bill’s current solution, to appoint a review judge to review every decision taken by the Rica judge on the same set of facts, does not fix the problem identified by the court, or improve oversight.

The Bill provides for a new layer of oversight in the form of a Review judge. The drafters have framed this as a solution to the Constitutional Court’s order that Rica must “adequately provide safeguards to address the fact that interception directions are sought and obtained ex parte”.

Unfortunately this solution does not address the problem. The problem identified by the Court is that, while the application to intercept someone’s communications excludes that person by necessity, this results in a one-sided process that makes it difficult for the Rica judge to consider all aspects. As the Court found:

[…] the result is that an application for an interception direction that may severely and irreparably infringe the privacy rights of the subject is granted on the basis of information provided only by the state agency requesting the direction. The designated judge is required to issue the direction on the basis of that one-sided information. Save perhaps for relatively obvious shortcomings, inaccuracies or even falsehoods, the designated judge is not in a position meaningfully to interrogate the information.[28] (Emphasis added)

In other words, this deficiency in Rica is not necessarily that the Rica judge may make poor decisions, but that the one-sided process limits their ability to perform their oversight fully. The solution proposed by the Bill is for a second judge (the review judge) to review all decisions taken by the first judge (the Rica judge) – but based on the same set of facts, in a similarly one-sided process. While we are not opposed in principle to the idea of an automatic review, it is unclear how this exact formulation will result in more thorough or inclusive oversight.

A proper solution to the ex parte problem is for the Bill to provide for a ‘public advocate’ whose role is to represent the interests of the surveillance subject in interception applications, and to ensure the Rica judge can hear ‘both sides’ of the matter. As documented in recent research by the Media Policy and Democracy Project, a growing number of jurisdictions have used this approach, often involving an advocate with security clearance, in order to ensure the right to a fair hearing in secret or security-related proceedings: these include the European Court of Human Rights, Canada, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom.[29] The Constitutional Court acknowledged this as a possible solution to the ex parte problem in Rica, but ruled Parliament should decide how best to fix it.

In addition to providing better oversight, the ‘public advocate’ solution may also provide more efficient oversight, by streamlining the process for judicial authorisations. In the Bill’s current formulation, every application must be heard first by the Rica judge, who must then refer their decision within five days to the review judge;[30] the review judge must then review that decision within five days.[31] In other words, the review process could extend the authorisation process by up to ten days – without meaningfully addressing the ex parte issue. By introducing a ‘public advocate’ to surveillance applications the Bill would address the ex parte issue and streamline the process to a single hearing.

Aligning ourselves to a similar proposal made in the submission by Professor Jane Duncan, we submit that the review process established in the Bill would be more appropriate if it occurs after the surveillance subject has been notified, in order to provide for their participation and for their views to be considered in the review.

Recommendations:

- The Bill should provide for a public advocate to participate in surveillance applications, in order to address the one-sided nature of these hearings. The current solution does not address the ex parte issue identified by the Constitutional Court.

- The automatic review process established in the Bill would be better served if it occurred after the subject of the surveillance has been notified and provided for their participation in the review.

- The Bill should provide for the appointment of multiple review judges.

2.4 PROVIDING AN APPROPRIATE TERM OF SERVICE

Summary: While we welcome the provision of a longer term of service for Rica judges, there are risks in the Bill’s proposal of a seven-year term. We support the recommendation of a five-year term.

The Bill provides for the designated judge and review judge to serve for up to seven years. Though the intention of the Bill is unclear, as no provision is made for a judge to be appointed for a term of less than seven years, we understand this to mean that a Rica judge will serve seven years unless they resign or die. While the provision of a longer term of office for Rica judges is appreciated, we align ourselves to research on international best practice for oversight of communications surveillance, which recommended that Rica judges serve for a fixed term of five years.[32] This recommendation was arrived at after a survey of various terms of office for specialised judges internationally and a recognition in international standards that overlong terms of service can result in “case hardening”, where a judge may lose their external insight as they become more conditioned to the culture and worldview of the intelligence services they oversee.

Recommendations:

- Rica judges (including review judges) should serve for a term of five years.

2.5 POST-SURVEILLANCE NOTIFICATION SHOULD NOT BE WATERED DOWN

Summary: We welcome the inclusion of the provision for post-surveillance notification – a feature that can be found in dozens of other countries’ interception laws. However, section 25A(2)b of the Bill waters down the court’s proposal by allowing for notification to be delayed indefinitely. The Bill also needs to provide a mechanism to ensure minimum standards and details for notification.

The Court’s interim relief included ‘reading in’ provisions to give effect to post-surveillance notification. These provide that people who have been targeted for surveillance should be notified within three months of an interception order having lapsed, but (acknowledging that premature notification could compromise an ongoing investigation, for example) also provided for the judge to grant a delay in the notification if law enforcement can show that it would jeopardise the purpose of the surveillance. Such delays may be granted for 90 days at a time, to a total of two years.

While the Bill does follow the Court’s order to provide for post-surveillance notification, there are two concerning aspects that increase the risk that surveillance subjects will not receive such notification within a reasonable time, or at all.

First, the Bill deviates from the Court’s interim provisions on post-surveillance notification with the addition of section 25A(2)b, which provides that:

“[if the notification] has the potential to impact negatively on national security, the designated judge may, upon application by a law enforcement officer, direct that the giving of notification be withheld for such period as may be determined by the designated judge.”

This creates the potential for notification to be withheld indefinitely, on the vague grounds of “national security”. In effect, it creates a loophole that may defeat the purpose of providing for post-surveillance notification in the first place.

Second, the Bill does not provide for any mechanism to ensure minimum standards, form, and detail for notification. The purpose of post-surveillance notification is to ensure that people who have been subject to surveillance have an opportunity to protect their rights and seek redress after the fact. A minimum level of detail is necessary to ensure this is a meaningful exercise, such as: the types of communication and data that were intercepted or accessed; the period during which interception took place; the agency that was responsible for the interception, the reason or purpose for which the interception order was granted; and guidance on access to further information or recourse.

The Bill also does not make it clear how and in what format the notification will be delivered to the surveillance subject. For instance, such notification could be delivered via email, post, text message, or in person by the responsible law enforcement officer.

Creating minimum requirements for the content and format of notification is especially important as notification is the responsibility of the same agency (and possibly even the same official) who did the surveillance. Under these circumstances the quality of the notification should not be left to individual discretion.

If the Bill does not provide clearly stipulated procedures for the delivery of post-surveillance notification notices, the content of these notices, and the recourse available should the surveillance subject wish to challenge the decision, there is a clear risk of notification becoming a meaningless exercise.

Recommendations:

- The Bill should prescribe a minimum level of detail, as outlined above, to be contained in the post-surveillance notification, and minimum standards for the delivery process and format of the notification and require strict adherence to such standards.

- Clause 25A2(b) should preferably be removed in its entirety. Alternatively, the same time limitations as in clause 25A2(A) must apply, and specific criteria for what constitutes grounds for delayed notification due to national security must be stipulated.

2.6 STRENGTHENING PROVISIONS FOR DATA MANAGEMENT RULES

Summary: Section 37A of the Bill seeks to address the Court’s finding that Rica must provide for procedures on the lawful handling, storing, and deletion of data acquired through interception – but effectively kicks the can down the road.

We align ourselves here to the observations and recommendations made by Professor Jane Duncan in her submission on the Rica Bill.

The Bill provides that data must be managed in a prescribed manner, but does not provide detail on how these will be prescribed. While we appreciate that certain operational details may be better dealt with through regulation, but the provisions appear to ‘kick the can down the road’ by not providing at least high-level guidance of how the procedures will be prescribed, and minimum requirements and standards for such procedures. Perhaps most importantly, if the issue is to be dealt with through regulation, there should be minimum requirements for public input and participation.

Recommendations:

- The Bill should provide clearer guidance on how data-management procedures will be prescribed, and either provide more binding detail of the procedures or ensure that the process for developing the procedures includes public participation.

2.7 PROVIDING FOR IMPROVED REPORTING AND PUBLIC OVERSIGHT

Summary: The inconsistent standards and detail in Rica judges’ statistical reporting on Rica has created longstanding challenges for Parliamentary and public oversight. Secrecy provisions in Rica have also discouraged service providers from disclosing interception statistics. The Bill should address this.

Reporting by the Rica judge

Ostensibly the requirement for Rica judges to submit an annual report on the functions of their office, including statistical information about interception decisions, is an important oversight feature. Unfortunately the inconsistent standards and detail in Rica judges’ reports has created longstanding challenges for Parliamentary and public oversight.[33] Across the terms of office of various past Rica judges, the reports – especially the statistical information – are often not comparable, as they sometimes covered different reporting periods (varying from 9 to 18 months) and sometimes omitted certain categories of data.

There are often also key details missing from reports; for example, although the judge’s report lists statistics related to how many and which type of interception directions were issued and which were rejected, there is no additional information stipulating exact reasons for rejection of applications. In addition, although Rica judges in the past have reported that there have been problems in confirming the veracity of applications for interception directions, no further details have ever been provided for specific cases.

Finally, because the Rica judge reports are tabled in the joint standing committee on intelligence, which typically opts to hold its hearings and documents in secret as a rule, there has often been a delay of up to 18 months in the report’s eventual publication in the National Assembly.

Establishing a standard for these reports, and ensuring they are tabled in open Parliament, would help the judges’ reports inform Parliamentary and public oversight.

Reporting by service providers

Although Rica does not explicitly prohibit network providers and ISPs from publishing statistics related to interception, section 42 of Rica (which prohibits disclosure of information obtained during an interception) has often been interpreted to this effect. As a result, service providers have often refused to disclose statistics about requests for interceptions and communication data access – d – despite an international trend among technology companies towards proactive disclosure of this type of information through annual ‘transparency reports’. This has similarly undermined public oversight.

Recommendation:

- The Bill should provide, through the office of the chief justice, for norms and standards for annual reporting by Rica judges, and for these reports to be tabled in open Parliament. The Bill should also mandate annual reporting on surveillance statistics by the agencies reporting to the Rica judge.

- The Bill should provide for service providers to publish annual disclosures of law enforcement requests for interceptions and access to communication data.

2.8 CONCERN ON RE-INTRODUCTION OF MASS INTERCEPTION IN A SEPARATE BILL

Summary: The Rica Bill rightly does not attempt to make bulk interception lawful, following the Court’s ruling that mass surveillance is not lawful in terms of Rica. However, we draw attention to a parallel legislative process, through the General Intelligence Laws Amendment Bill, which would create a parallel ‘bulk interception’ regime that undermines this committee’s work.

The Bill – rightly – does not seek to regularise or re-introduce the state’s bulk interception or mass surveillance powers which the Court declared to be unlawful in terms of Rica. However, we draw the committee’s attention to the parallel policy process unfolding in terms of the General Intelligence Laws Amendment Bill (the GILAB) 2023, which seeks to do this.

The GILAB would set up a parallel surveillance framework with none of these safeguards provided in Rica, such as they are, or the additional safeguards required by the Constitutional Court judgement in amaBhungane.

Historically, bulk or mass communications interception has been carried out by the State Security Agency (SSA) and its predecessors at a facility known as the National Communications Centre (NCC). The NCC’s reported capabilities amounted to a mass surveillance facility, scanning millions of communication signals in order to identify people or groups to be targeted for further surveillance. This constitutes an inherently untargeted infringement on privacy: large numbers of persons who are not under any suspicion of wrongdoing were caught in a surveillance dragnet, without their knowledge or permission, or any legal framework. Because the NCC has the technical capability to carry out interception of communications (either of millions of people or of a single individual) without the technical assistance of the service provider, this resulted in the Rica judge being bypassed.

Because Rica does not provide for such powers (nor should it) the Constitutional Court declared these activities to be unlawful.

The GILAB attempts to regularise these powers by introducing them into law, but in doing so would create a parallel interception procedure that greatly undermines efforts to reform Rica. In terms of the GILAB, the NCC would resume its mass surveillance system, with nominal oversight from a judge, who would be appointed by the President and advised by two ‘interception experts’ appointed by the intelligence minister. This falls far short of the standards for surveillance oversight set by the Constitutional Court, which demands sufficient independence of judges authorising surveillance.

The Gilab also does not provide for the requisite protections for privacy and freedom of expression, nor for meaningful oversight of the NCC, or any of the other safeguards that are provided for in Rica and the Court in amaBhungane. While we appreciate the Gilab falls outside the justice committee’s scope, we draw attention to it as its provisions would seriously undermine efforts to reform Rica and address the Constitutional Court’s ruling.

Recommendation:

- The GILAB should be withdrawn, and Rica should remain the only law governing interceptions.

- Any surveillance powers wielded by the state must align to the international standards established in the 2014 ‘Necessary and Proportionate’ principles, which requires that they are targeted, sufficiently constrained, and subject to rigorous independent oversight and controls.

3. CONCLUSION

We are aware that the Department has argued that the extreme delay in tabling this Bill has left no time to address reforms that were not explicitly ordered by the Constitutional Court. This may invite the argument that Parliament should pass this Bill now with minimal amendments in order to meet the Court’s deadline, and consider other reforms at some later stage.

The question is: If not now, when?

The Department of Justice has pledged to address these issues for years. When some of the matters were brought to court, the Department first argued that they should be dealt with by policymaking processes rather than litigation; then, in the Constitutional Court, the Department successfully argued that it would need three years, rather than two, to undertake a comprehensive reform. Yet years later it has introduced bare-minimum reforms, and only with a court-imposed deadline looming.

There is little reason to hope that these other vital reforms will be dealt with in follow-up amendments anytime soon.

Regrettably, these events send a message that the only way to achieve these kinds of reforms is under threat of litigation. We share the view that law and policy are best made through the democratic processes of the legislature, rather than through the courts. We therefore urge the committee to ensure this amendment Bill delivers comprehensive reforms to Rica, and ensures the legal loopholes that have enabled surveillance abuses are closed once and for all.

We thank the committee for its consideration, and remain available to provide further detail on the issues raised here, and to make a verbal presentation.

Ends.

4. REFERENCES

[1] amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism NPC and Another v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others; Minister of Police v amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism NPC and Others (CCT 278/19; CCT 279/19) [2021] ZACC 3

[2] International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance (2014). (Available here.)

[3] See for example J Duncan, ‘Communications Surveillance in South Africa: The Case of the Sunday Times Newspaper’ in Global Information Society Watch 2014: Communications Surveillance in the Digital Age (2014) (Available here) and M Hunter and T Smith, Spooked: Surveillance of Journalists in South Africa, Right2Know Campaign (July 2018). (Available here.)

[4] See for example, Office of the Inspector General of Intelligence ‘Executive summary on the final report on the findings of an investigation into the legality of the surveillance operations carried out by the NIA on Mr S Macozoma’ (23 March 2006). (Available here.)

[5] Report of the High-Level Review Panel on the State Security Agency (2019), at 65-66.

[6] A Mare and J Duncan An Analysis of the Communications Surveillance Legislative Framework in South Africa, Media Policy and Democracy Project, November 2015. (Available here.)

[7] M Hunter Cops and call records: policing and metadata in South Africa. Media Policy and Democracy Project, 27 March 2020. (Available here).

[8] C Kruyer, Reforming communication surveillance in South Africa: recommendations in the wake of the amaBhungane judgment and beyond. Johannesburg, Intelwatch & Media Policy and Democracy Project, 2023 (Available here.); H Swart Supplementary report: Understanding the section 205 loophole, Intelwatch, 2023. (Available here.)

[9] Annual Report by the designated Rica judge on the Interception of Private Communications for the Period 2014/2015 to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence (October 2015) at para 9.1. (Available here.)

[10] The list of amendments reportedly under consideration are worth listing in full. They include:

- Facilitating an electronic process for applications for directions and service of directions contemplated in Chapter 3 of the Rica;

- Ensuring the integrity of the process of obtaining customer information;

- Further regulating listed equipment provided for in sections 44, 45 and 46 of the Rica;

- Complimenting information sharing between electronic communications service providers and Government agencies;

- Further providing for interception capabilities of law enforcement agencies;

- Imposing obligations on electronic communications service providers who provide an internet service to record and store call related information;

- Appointing a regulatory body to ensure compliance with the Rica by the electronic communications service providers;

- A review of terminology used in the Rica to address interpretation of problems which were being experienced; and

- Addressing problems with the implementation of provisions for the Rica registration process (section 40) where the particulars of customers are incorrectly captured.

[11] H Swart ‘Big Brother is watching your phone call records,’ Daily Maverick (10 May 2017). (Available here.)

[12] Parliamentary Question No. 1371, 5 June 2017. (Available here.)

[13] First respondent’s answering affidavit, 8 March 2018. Amabhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism NPC and Another v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others (25978/2017) ZAGPPHC

[14] For a more detailed analysis of these challenges, see H Swart Supplementary report: Understanding the section 205 loophole, Intelwatch, 2023. (Available here.)

[15] South African Law Commission Report on project 105: Review of Security Legislation, the Interception and Monitoring Prohibition Act 127 of 1992 (October 1999) at 25.

[16] Rica prescribes that applicants must be: for SAPS, a commissioned officer (colonels, lieutenant-colonel, major, captain or lieutenant) with written approval from a senior official with at least the rank of Major-General; for the intelligence services, any member with written permission from someone with at least the role of general manager; for the SANDF, a commissioned officer with written approval from a senior official with at least the rank of Major-General, and so on.

[17] The full list of offences in which a Rica interception may be sought is more than a page long, but broadly includes violent offences (anything which might result in someone’s death), offences stemming from organised crime and racketeering, and crimes against the state such as treason or terrorism.

[18] Hunter, 2020 at 4.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Whereas the Bill refers almost exclusively to “the designated judge” in singular, the existing Act generally refers to “a designated judge” as a category of judges rather than a singular role (the term “a designated judge” appears 34 times). Section 58(1) of the existing Act explicitly refers to “a designated judge or, if there is more than one designated judge, all the designated judges”.

[21] Annual Report by the designated Rica judge on the Interception of Private Communications for the Period 2014/2015 to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence (October 2015) at 14.1 – 14.9.

[22] H Swart ‘Rica’s toothless watchdogs: The awful state of SA’s lawful telecoms interception, Part One,’ Daily Maverick (12 July 2022). (Available here.)

[23] Annual Report by the designated Rica judge on Interception of Private Communications for the Period 1 November 2018 to 28 February 2021 to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence (March 2021) at 40.

[24] Annual Report of the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence (JSCI) for the financial year ended 31 March 2008 (12 May 2010) at para 4.4.

[25] Annual Report by the designated Rica judge on the Interception of Private Communications for the Period 1 November 2018 to 28 February 2021 to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence (March 2021) at 40.

[26] Annual Report by the designated Rica judge on the Interception of Private Communications for the Period 2014/2015 to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence (October 2015) at 14.8 – 14.9.

[27] See Hunter, 2020, at 25.

[28] amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism NPC and Another v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others; Minister of Police v amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism NPC and Others (CCT 278/19; CCT 279/19) [2021] ZACC 3; 2021 (4) BCLR 349 (CC); 2021 (3) SA 246 (CC) (4 February 2021).

[29] Kruyer, at 18.

[30] Section 15A(5). The exception to this is applications in terms of section 23 of Rica, which provides for security officials to make an oral application for interception in emergency situations; the Bill requires the Rica judge and review judge to consider these immediately.

[31] Section 15C(1).

[32] Kruyer, at 16.

[33] See J Duncan, Stopping the Spies: Constructing and Resisting the Surveillance State in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2018, at 98-101.

Download the submission as a PDF here.